Food labeling is kind of a messy issue right now. On one side you have advocates of “Right to Know” fighting for GMO-containing products to be labeled as such. On the other side you have soda companies and fast food restaurants digging in their heels to fight laws that would require further nutrition information posted on vending machines and menu boards.

From this perspective, it seems there’s plenty of push and pull in this important debate. The worst part, however, is that the consumer is caught in the middle with the simple desire to know what’s in the food they buy and to feel good about what they put in their bodies.

While the discussion of food labeling may have multiple sides and a variety of opinions, an editorial piece by Mark Bittman published in The New York Times Saturday shined some much-needed light on the topic and offered a simple solution: Make labels honest, easy to read and understand, and useful to the health-conscious consumer.

Bittman’s idea of a “dream food label” is no longer just a dream. The NY Times writer and health advocate has been working with Werner Design Werks in St. Paul, Minnesota to develop a new template for food labels that would essentially remove the less-important items on current food labels and add useful information to help the consumer answer the simple question, “Is this product honestly healthy?”

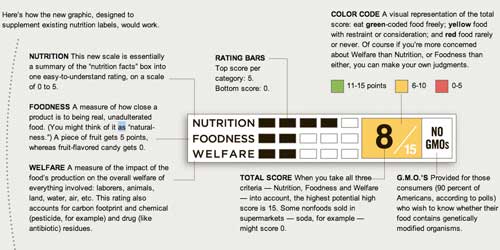

The proposed label would consist of a color-coded bar based on a 15-point scale. If the food’s ranking falls between 11 and 5, it would be green; between 6 and 10, yellow; and between 0 and 6, red. The ranking is determined by three key factors: “Nutrition,” “Foodness” and “Welfare.” Nutrition is based on but not limited to the amount of sugar, trans fats, fiber and micronutrients the product contains. For example, a product such as soda would be given a zero in Nutrition while a bag of fresh spinach might receive a 5.

When ranking a food based on its “Foodness,” this essentially means it’s being assessed on whether or not the product is real or fake. The assessment would be based on if the product is made with things like bleached flour, yeast conditioners or preservatives. For example, a candy bar would be likely to receive a zero rating, whereas fresh fruit would receive a 5.

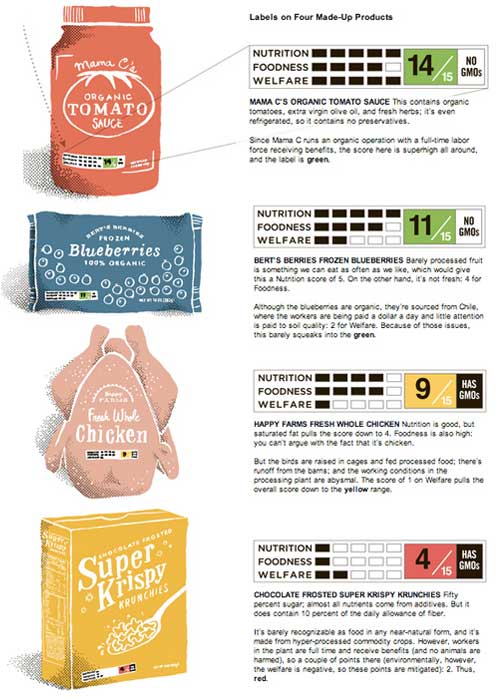

Lastly, the “Welfare” ranking of the product is based on the treatment of the workers and animals involved in production, and its impact on the earth. Some of the questions Bittman suggests this ranking might answer include: “Is environmental damage significant? Are workers treated like animals? Are animals produced like widgets?” ‘Yes’ answers to all of these questions would put the ranking near a zero. However, if the workers and animals involved in production were treated fairly and the product didn’t cause significant waste or environmental damage, the ranking would be closer to a 5. This illustration from The Times provides a great example of how various foods would stack up using the new system.

Bittman believes this new labeling system would be a key tool in the fight against obesity, allowing consumers to make more conscious decisions about the food they consume. Beyond just knowing whether or not a food will make us fat, Bittman contends that the addition of “Foodness” and “Welfare” raise the bar even more, alerting consumers to things like whether or not the food was produced in an environmentally conscious way and if it contains pesticides.

As reported by The Times, the possibility of this style of labeling actually being implementing is closer than we may think. For instance, a traffic-light labeling system almost passed in Britain this summer, and the U.S. Institute of Medicine has proposed a similar system outlined in this report.

If adopted, there’s no guarantee that this label would reverse or even have an impact on the obesity epidemic in our country. However, it would be big step in the right direction, finally holding food producers accountable for the quality of their products and informing consumers of what’s in the products they buy.

While Bittman admits the rating system is not a simple one that can be easily applied to all foods, he argues it’s not impossible. If it meant a healthier nation and the availability of more whole, healthy and honest foods, we think it would be well worth the effort.

Also Read:

Major Organic Brands, Like Kashi and Naked, Funding Anti-GMO Labeling Campaigns

Four Simple Tips for Avoiding GMOs

California’s Push for Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods

images via The New York Times